PhD dissertation

2025, 26 October

2022, 29 September

Written by Thirza Dado & Umut Güçlü.

The uncanny cliff hypothesizes that artificial figures remain either on the cliff (i.e., perceived as human-like) or they fall from the cliff (i.e., perceived as fake with disturbing feelings of eeriness and unease).

The uncanny cliff hypothesizes that artificial figures remain either on the cliff (i.e., perceived as human-like) or they fall from the cliff (i.e., perceived as fake with disturbing feelings of eeriness and unease).

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are powerful generative models trained to synthesize (“fake”) data that seem indistinguishable from “real” data. A recent study demonstrated with an experiment how GANs can be used to reconstruct literal pictures of what volunteers in the brain scanner were seeing by neural decoding of their brain recordings. Concretely, these volunteers were looking at pictures of faces of people; faces that do not really exist but are instead synthesized by a 🤖Progressively Grown GAN (PGGAN) for faces.

The goal of neural decoding is to discover what information (about a stimulus) is present in the brain. That said, any property of a stimulus could potentially be decoded from the brain.

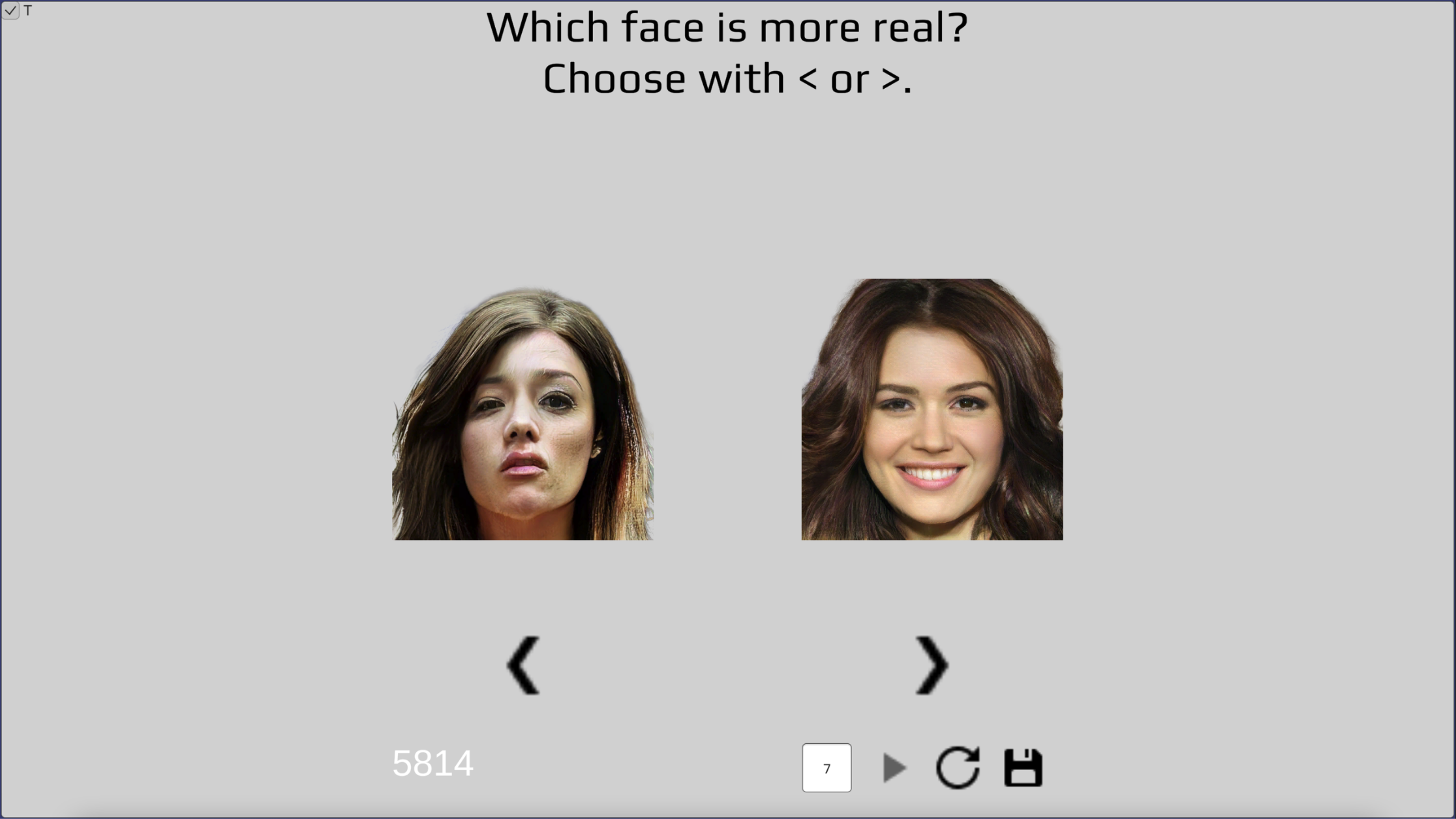

A selection of faces from the used dataset illustrates that some faces look more natural or real and some faces look more fake. We call this property “syntheticity”.

A selection of faces from the used dataset illustrates that some faces look more natural or real and some faces look more fake. We call this property “syntheticity”.

Although the presented faces in the experiment look hyperreal to human observers in general (but are all fake and do not exist), close inspection of the used face stimuli revealed that some faces look less real than others, resulting in disturbing feelings of eeriness and unease. That is, these data have a property of “syntheticity” that denotes how real or fake a face looks.

The uncanny valley theory hypothesizes that the affinity response of a human observer towards an artificial figure becomes more and more positive when it looks more and more human-like but up to a certain point where it abruptly switches from empathy to revulsion. Alternatively, it has been proposed that the valley is more like an uncanny cliff:

“We are not certain if this section [of the uncanny valley between the deepest dip and the human level] actually exists thereby prompting us to suggest that the uncanny valley should be considered more of a cliff than a valley, where robots strongly resembling humans could either fall from the cliff or they could be perceived as being human.”

Bartneck, C., Kanda, T., Ishiguro, H., & Hagita, N. (2007)

Here, we will decode syntheticity from neural data and see whether the results indicate a gradient or a cliff!

Behavioral experiment to sort faces on syntheticity.

Behavioral experiment to sort faces on syntheticity.

To quantify the behavioral phenomenon of perceived syntheticity, we can do a behavioral experiment where a volunteer attributes syntheticity scores to all the faces. Concretely, the volunteer (i.e., me, I volunteered) sees two face images at a time and is asked “which face looks more real” and, if this question was too difficult to answer, “which face do you like better”. As such, the faces get scored on syntheticity and we can sort them from real- to fake-looking.

To be more efficient than presenting combinations of face pairs with a worst-case performance of O(n²) with n=1086, we can go and implement the divide and conquer merge sort algorithm that iteratively merges smaller lists of sorted images until one big sorted list of fake-to-real-looking faces remains. This algorithm sorts each face in relation to other faces but not all the other faces because we can already infer knowledge from earlier decisions, resulting in a worst-case bound of O(n log n) (i.e., it still took me three days to make 10136 comparisons😬). The experiment was implemented in Unity and C#.

You can find the result files here: ridx contains the initial (unsorted) index order that determined which pair of faces would be presented to the screen and sidx is the index list sorted on syntheticity by the volunteer. That is, we sort the original ridx by the “sorted” sidx. In the last for-loop in the code snippet below, we then sort again from 0 to 1086 (fake- to real-looking).

with open(path + "sidx_T_7_10136.txt") as f:

sidx = np.array([ int(i) for i in f ])

with open(path + "ridx_T_7_10136.txt") as f:

ridx = np.array([ int(i) for i in f ])[:len(sidx)]

sorted = ridx[sidx]

scores = np.zeros(1086)

for i in range(1086):

scores[i] = np.where(sorted == i)[0]

We use the hyper dataset of fMRI measurements to PGGAN-generated face stimuli (whole dataset). In this blog post, we use the same 4096-voxel selection as the original hyper study which can be found here but it would also be interesting to have a look at whole-brain or different brain areas. Let’s hyperalign and average the brain data of the two participants (just like we did in a previous blog post). Alternatively, you can also just pick the brain responses of either subject 1 or 2.

! apt-get install swig

! pip install -U pymvpa2

import mvpa2.datasets

import mvpa2.algorithms.hyperalignment

import numpy as np

import pickle

def hyperalignment(a, b):

x = [a, b]

dataset = [mvpa2.datasets.Dataset(x_) for x_ in x]

hyperalignment = mvpa2.algorithms.hyperalignment.Hyperalignment()(dataset)

y = [hyperalignment[j].forward(dataset[j]).samples for j in range(len(dataset))]

return (y[0] + y[1]) / 2

path = "/yourpath/"

with open(path + "data_1.dat", 'rb') as f:

X_tr1, _, X_te1, _ = pickle.load(f)

with open(path + "data_2.dat", 'rb') as f:

X_tr2, _, X_te2, _ = pickle.load(f)

X_1 = np.array(X_te1 + X_tr1)

X_2 = np.array(X_te2 + X_tr2)

X = hyperalignment(X_1, X_2)

We do a linear mapping from brain responses to syntheticity scores. The original dataset order (test + train) is permuted to ensure various degrees of syntheticity because the quality in the original test set (36 faces) was quite good. The syntheticity scores in the test set would otherwise all be more or less similar (i.e., very real-looking). We use a 90:10 split where 90% of the data is used as the training set and the remaining 10% is used as the held-out test set to evaluate model performance.

from scipy.stats import zscore

np.random.seed(1)

permutation = np.random.permutation(1086)

_X = X[permutation]

_T = scores[permutation]

n = int(1086 / 100 * 10)

x_te = zscore(_X[:n])

x_tr = zscore(_X[n:])

t_te = zscore(_T[:n])

t_tr = zscore(_T[n:])

reg = LinearRegression().fit(x_tr, t_tr)

y_te = reg.predict(x_te)

To evaluate the model performance of our linear decoder, we can look at the correlation between the predicted scores from brain data and the syntheticity scores from the behavioral experiment.

from scipy import stats

from scipy.stats import t

def pearson_correlation_coefficient(x: np.ndarray, y: np.ndarray, axis: int) -> np.ndarray:

r = (np.nan_to_num(stats.zscore(x)) * np.nan_to_num(stats.zscore(y))).mean(axis)

p = 2 * t.sf(np.abs(r / np.sqrt((1 - r ** 2) / (x.shape[0] - 2))), x.shape[0] - 2)

return r, p

r, p = pearson_correlation_coefficient(y_te, t_te, 0)

print(r.mean(), p.mean())

This results in r=0.4298, p=3.46e-06, meaning that we can indeed predict continuous syntheticity scores from the fMRI recordings from the hyper experiment. This means that the neural representations of the perceived faces contain continuous- rather than binary information on syntheticity. Otherwise, if the encoded information would have been binary (i.e., either real- or fake-looking), it would not have been possible to decode these continuous values from the brain. In conclusion, our result supports the uncanny valley theory rather than the uncanny cliff.

It would be cool to make comparisons with other metrics such as feature maps and/or (classification) scores of discriminator networks. Further, we could also use a searchlight to identify where and with what magnitude syntheticity is encoded in the brain.

That’s all.

2025, 26 October

2025, 17 July

2024, 05 January

2023, 01 November

2023, 12 July

2021, 07 April

2021, 07 March

2021, 07 February